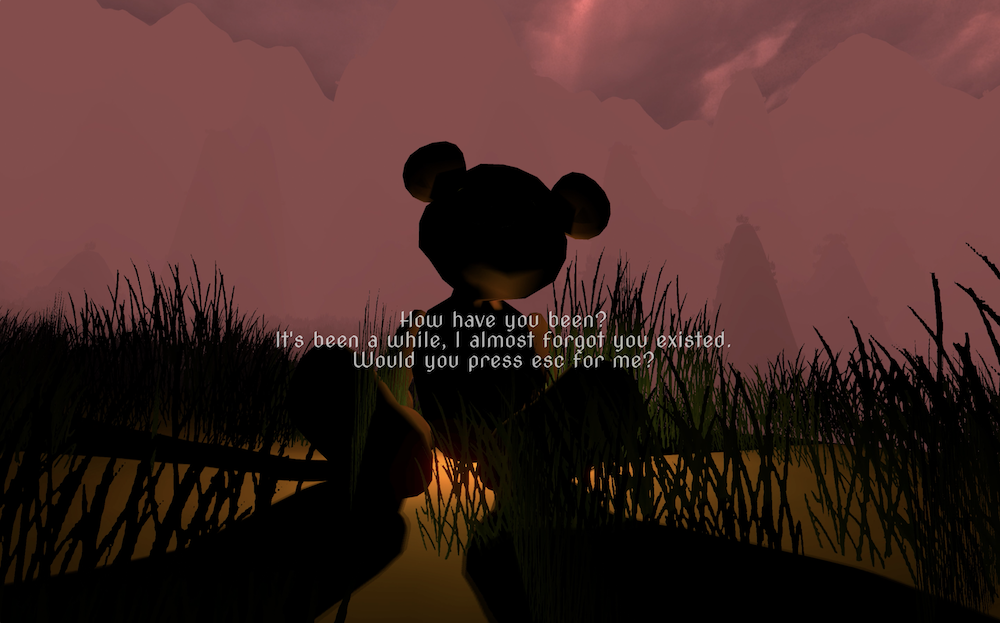

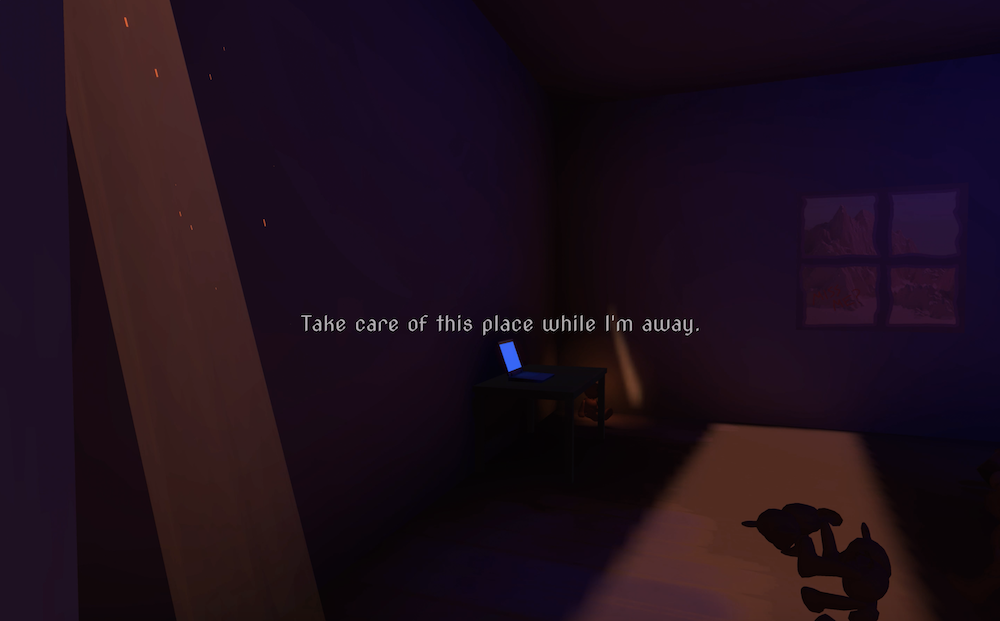

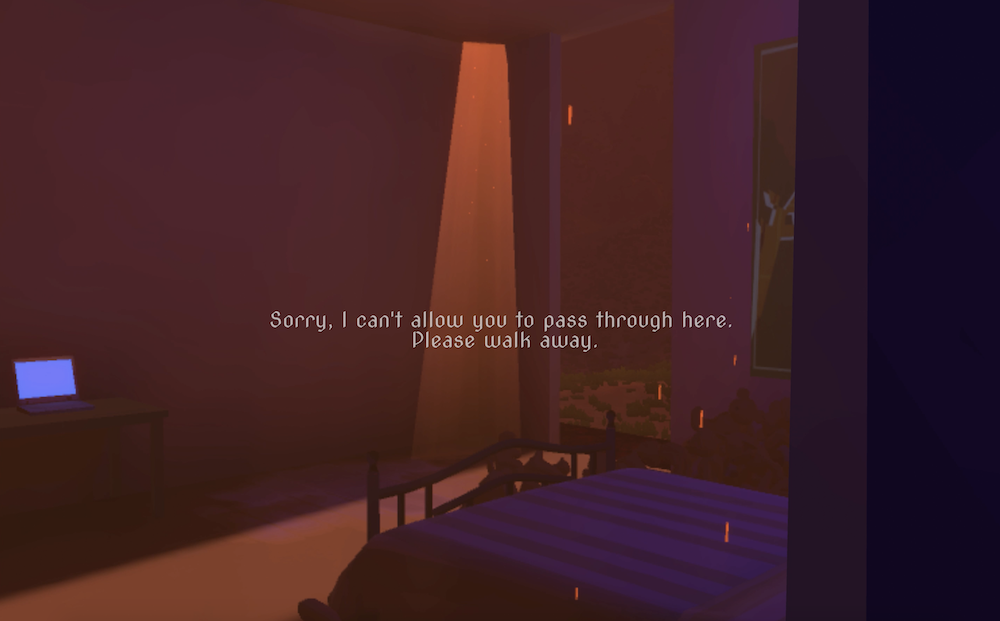

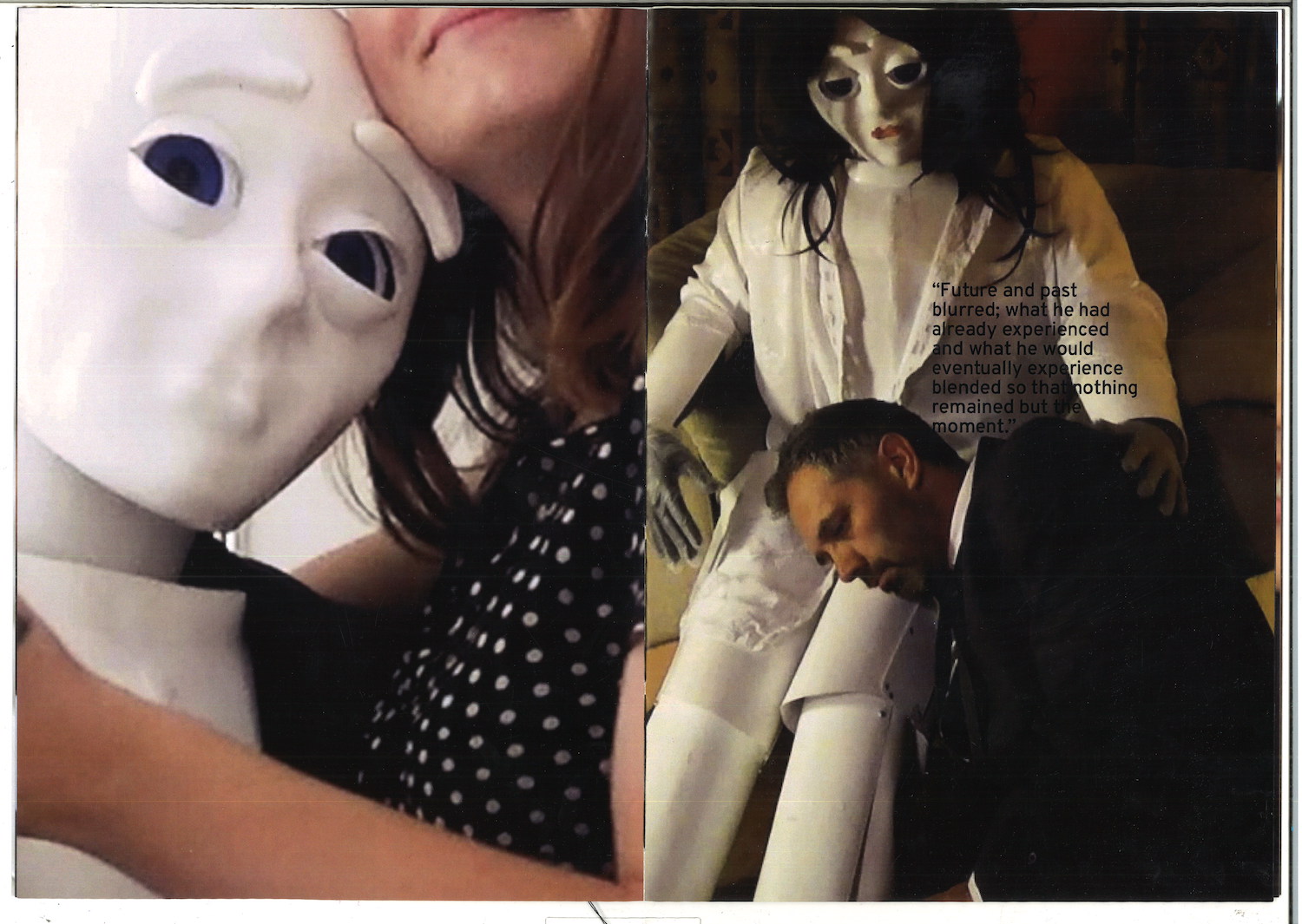

2020(...) frozen in time and place as we are, an escape experience that leads to nowhere, a different digital insight in our bedrooms than what we’ve gotten used to in the past year.

A game that travels through the individualised but globally relatable feeling of the year(s) 2020. A hybrid interactive time capsule of our isolation bedrooms.

Built collectively with <Louise Huyghe> and <Sarah Khadra Hasni>.

See full gameplay <here>

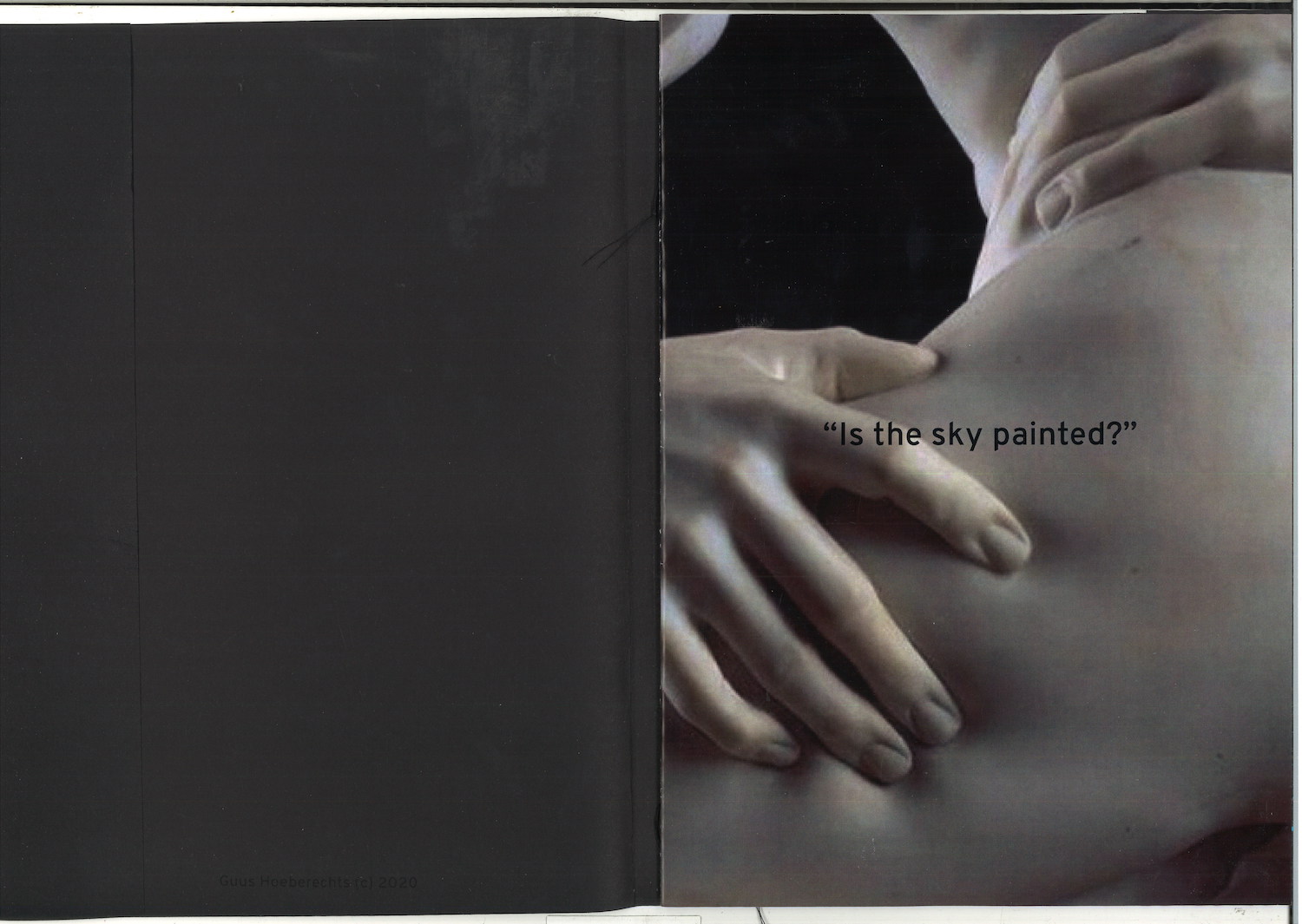

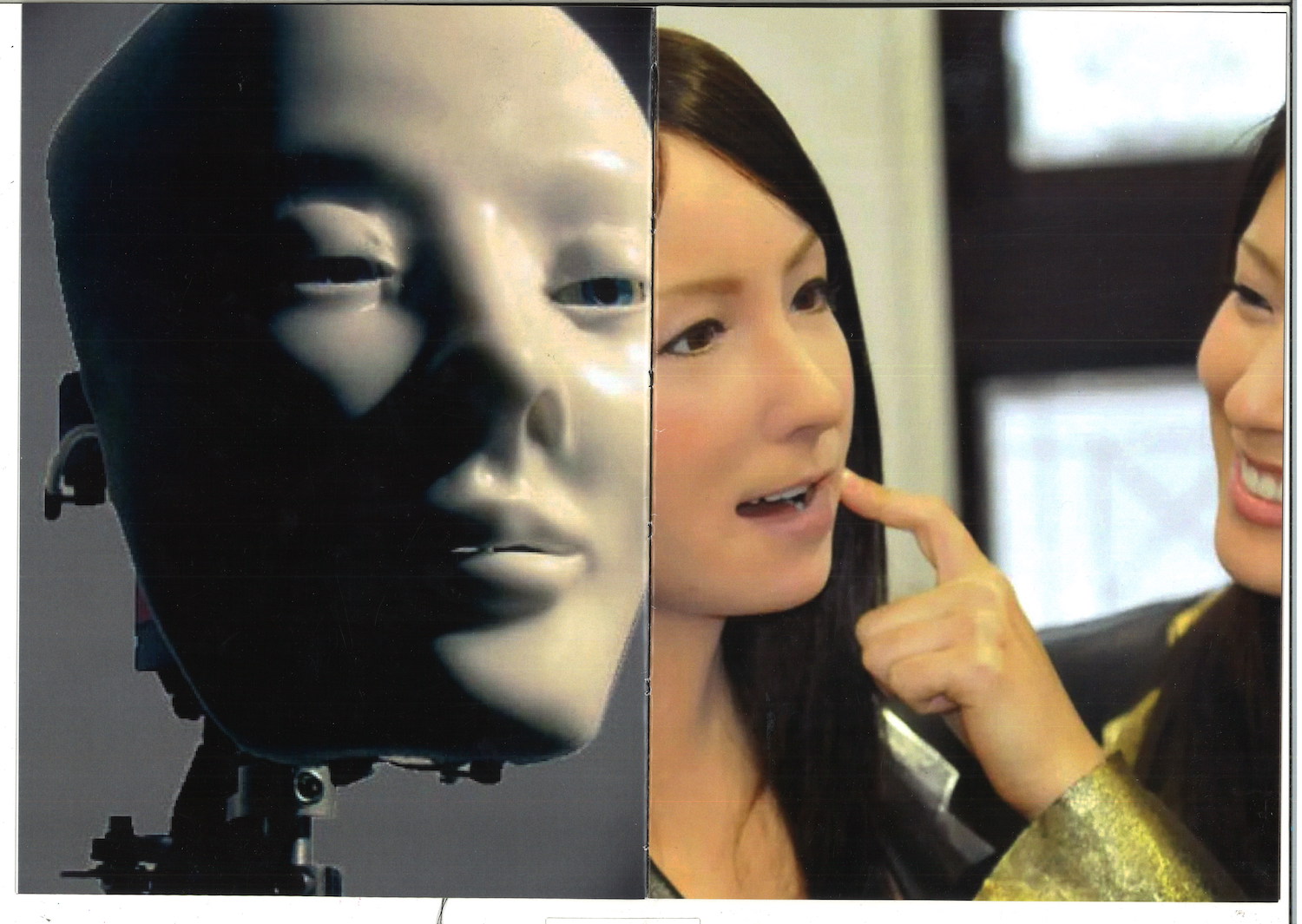

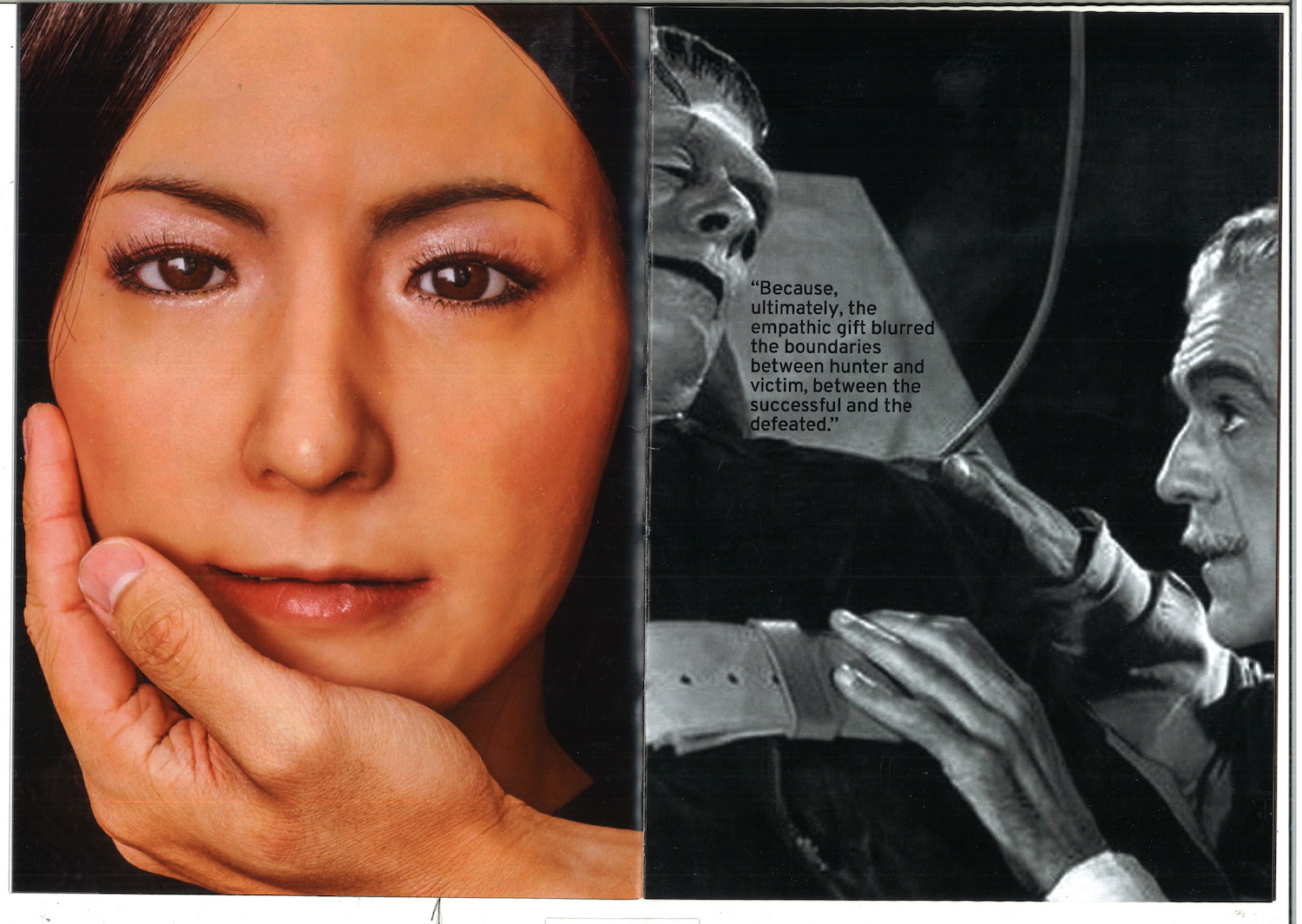

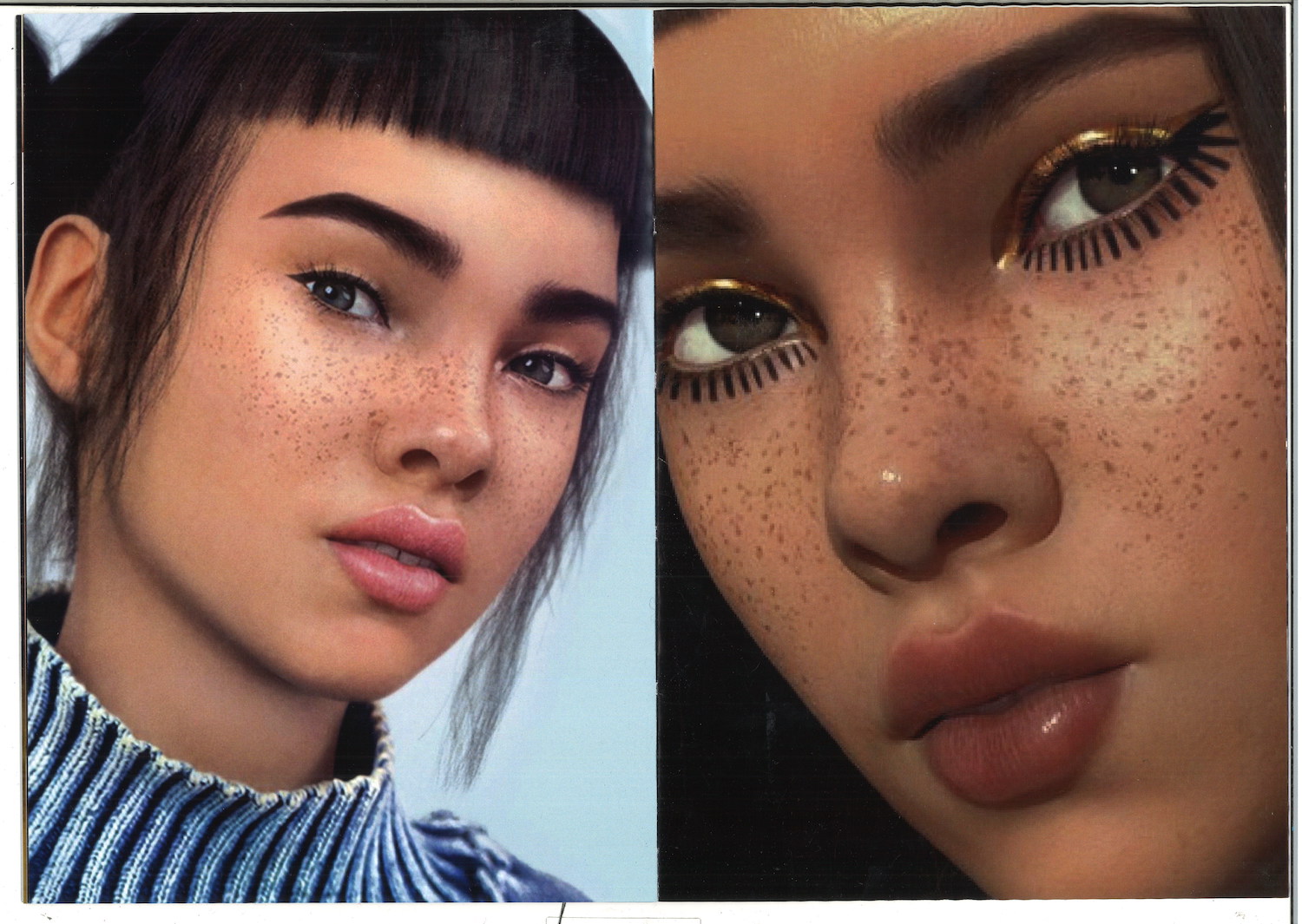

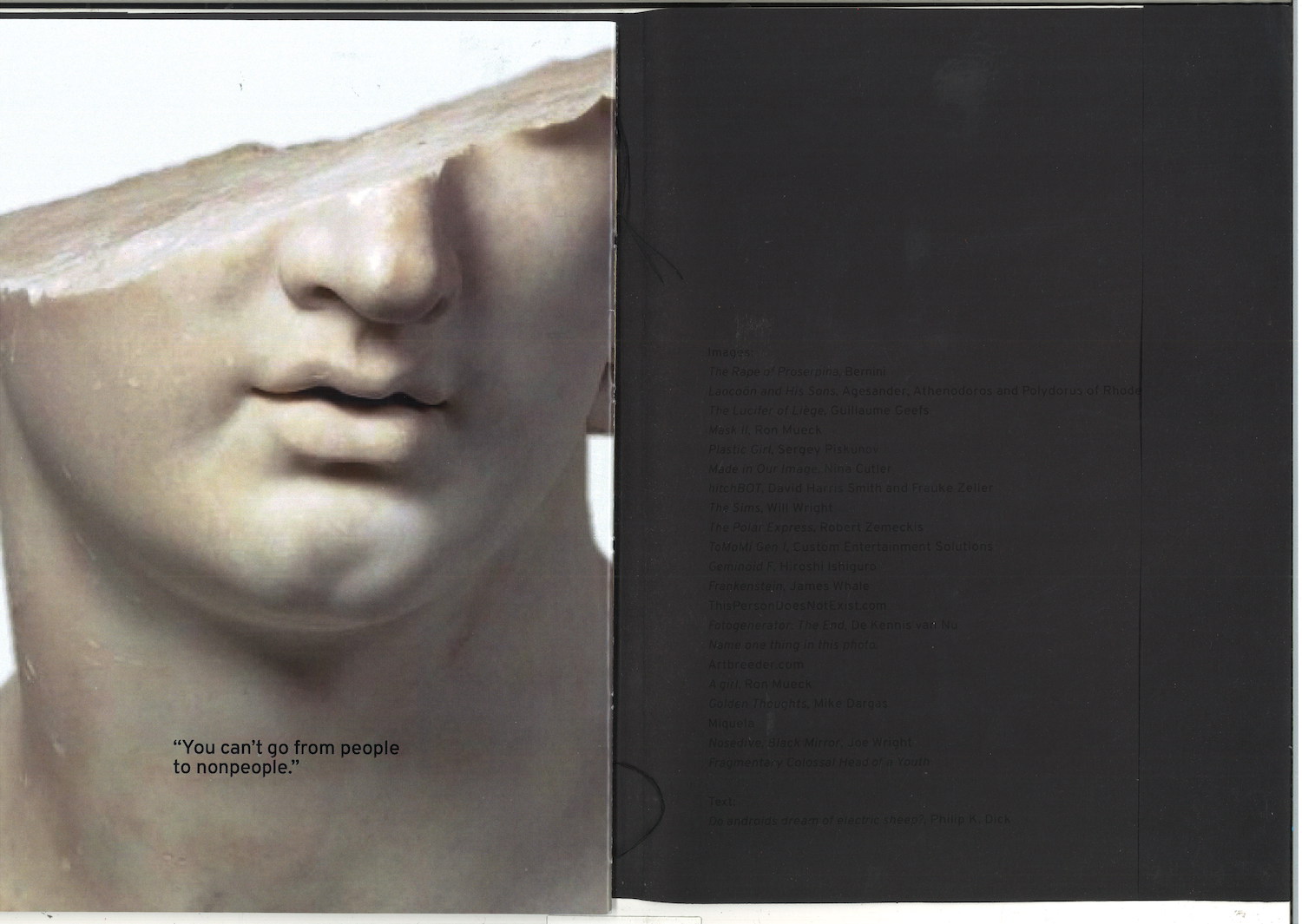

We are surrounding ourselves with artificial presentations of humanity. We bond to these, we form relationships, we care for them. We love them. We help them come alive, and in return they help us live. How far can we go, before we’ve lost our original humanity? Will we be able to tell apart the man-made from the man? What happens when we replace life with objects?

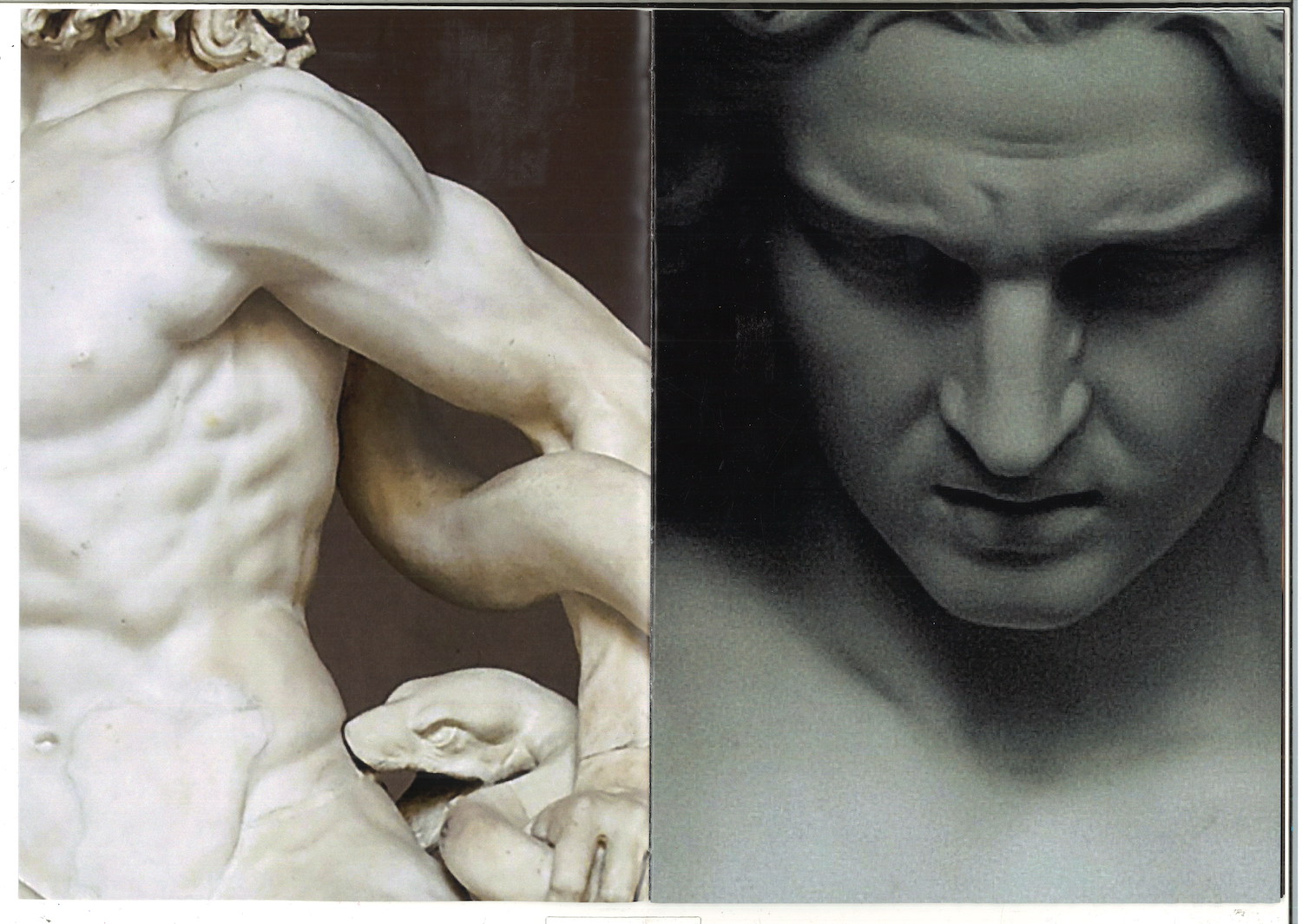

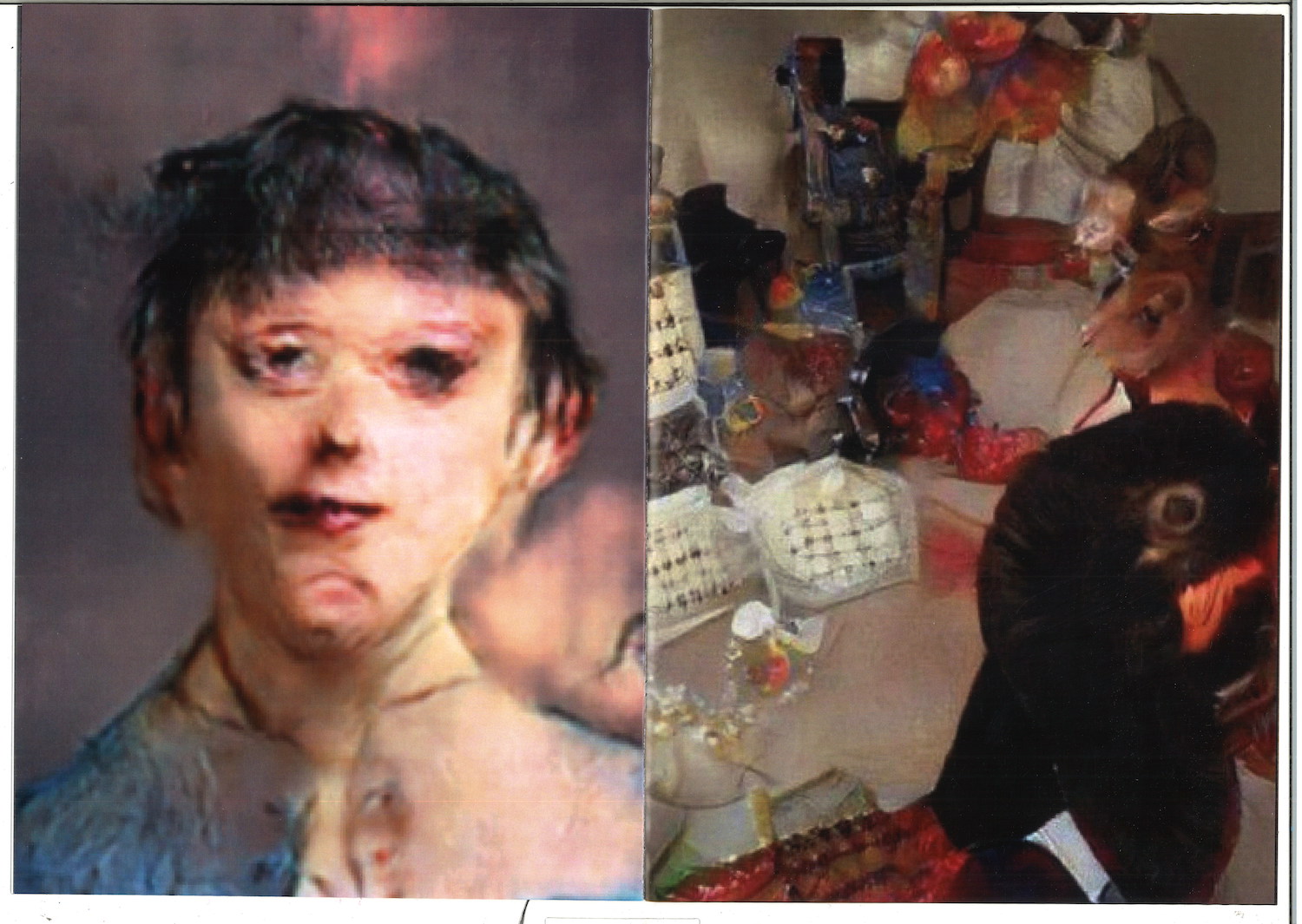

We are made up of dimensions, layers beneath our skin that shape the way we are. The different worlds within us grow our identities and our souls meet where their veil spreads too thin for separation. We contain multitudes of ourselves.

Within the outer world, we perform our existence. We make up which of our souls get to see the daylight and which we hide under layers of translucence, in the ghostly corners of our bodies, buried deeper and deeper within us. A fabricated life, for an artificial world, where reality and non-reality blurred their lines long ago.

Mystery surrounds our inner world, the workings of our life. We live a counterfeit story in a pseudo-culture of shared psyches. When we don’t feign, what souls do we put forward? When we don’t feign, who are we?

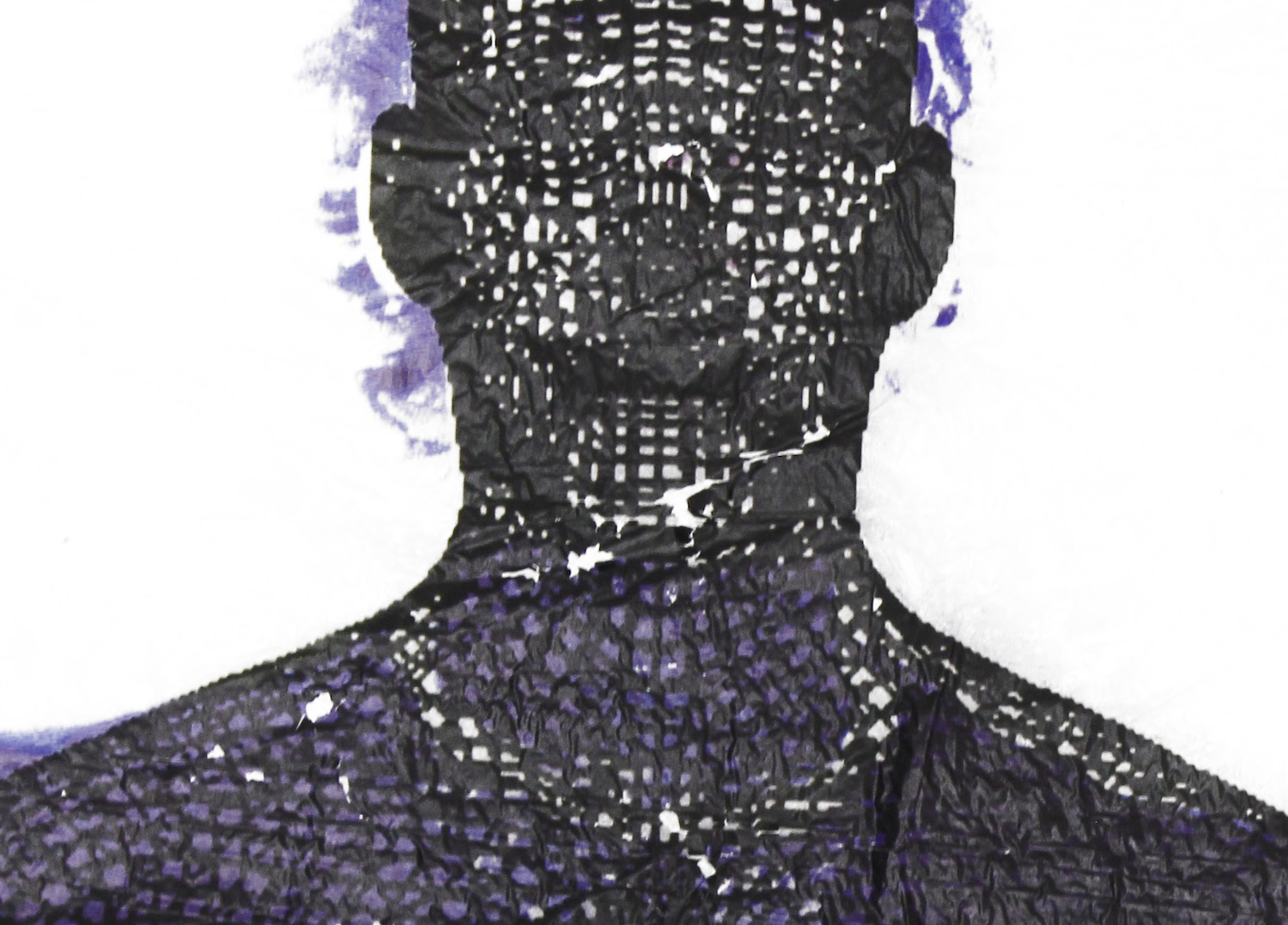

As a spectator of the swift rise of technology, our generation has been influenced by this phenomenon more than any. It returns in all aspects of life and determines our way of thinking, even that of the subconscious.

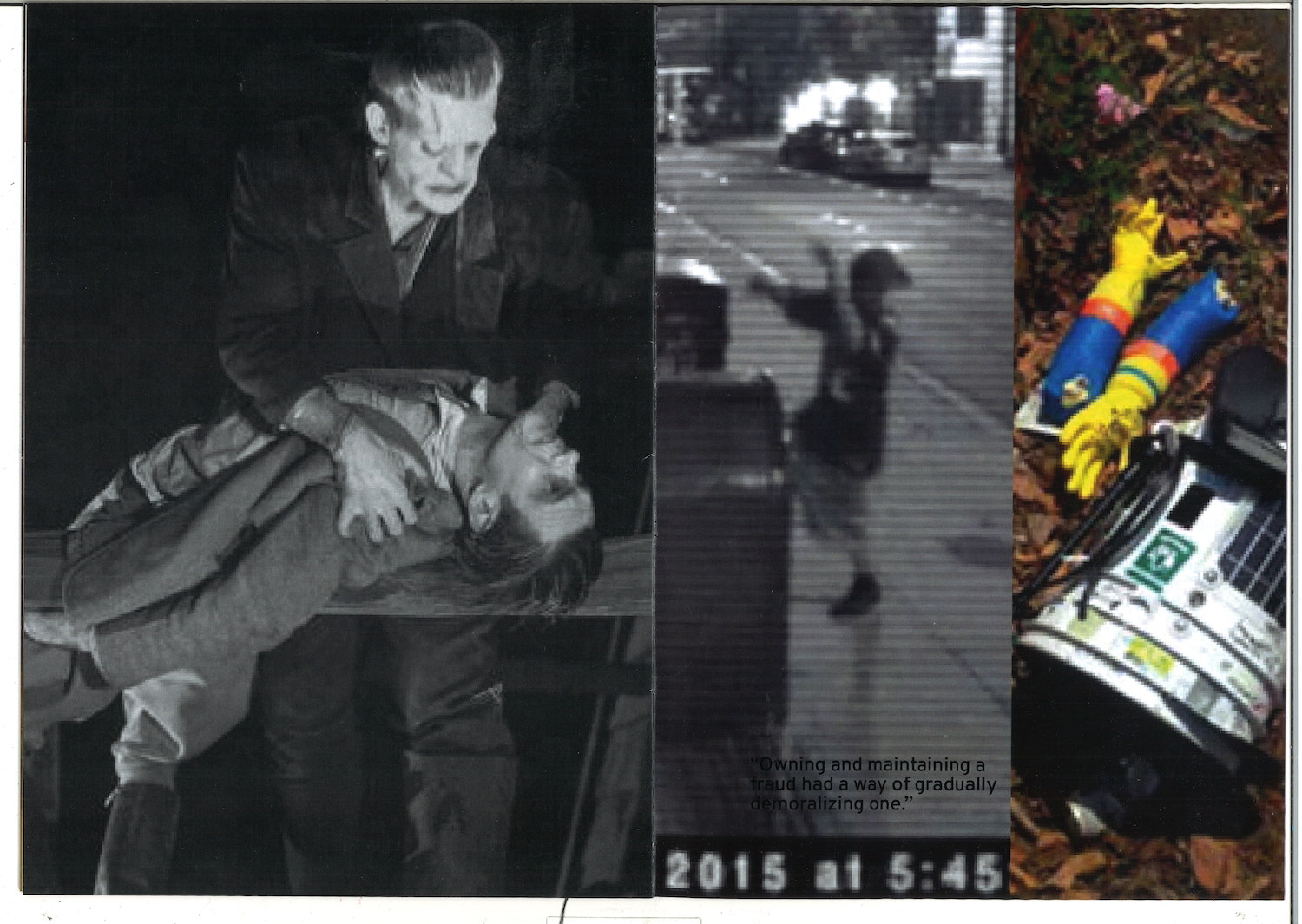

The lands of dream, memory, technology, childhood and adulthood come together in this video to create a storyline that features fear, confusion and acceptance. By text and image, the viewer is led through the complex world of dreams and reality in the digital age.

The created space is a liminal one, where you are disoriented from the rest of the world until you step foot over the threshold back into reality. This dimension is in-between, fluid to your own perception. The flowers obstruct full vision of the room, they command you to be here, now, yet confuse you to where you are. Time and space are subjective here.

We are in a permanent liminality of modernity, forever changing, forever in- between, the grey area of all things innovating and still remaining the same. Between the real and the pretend, the analogue and the digital, the alive and the dead, without direction.

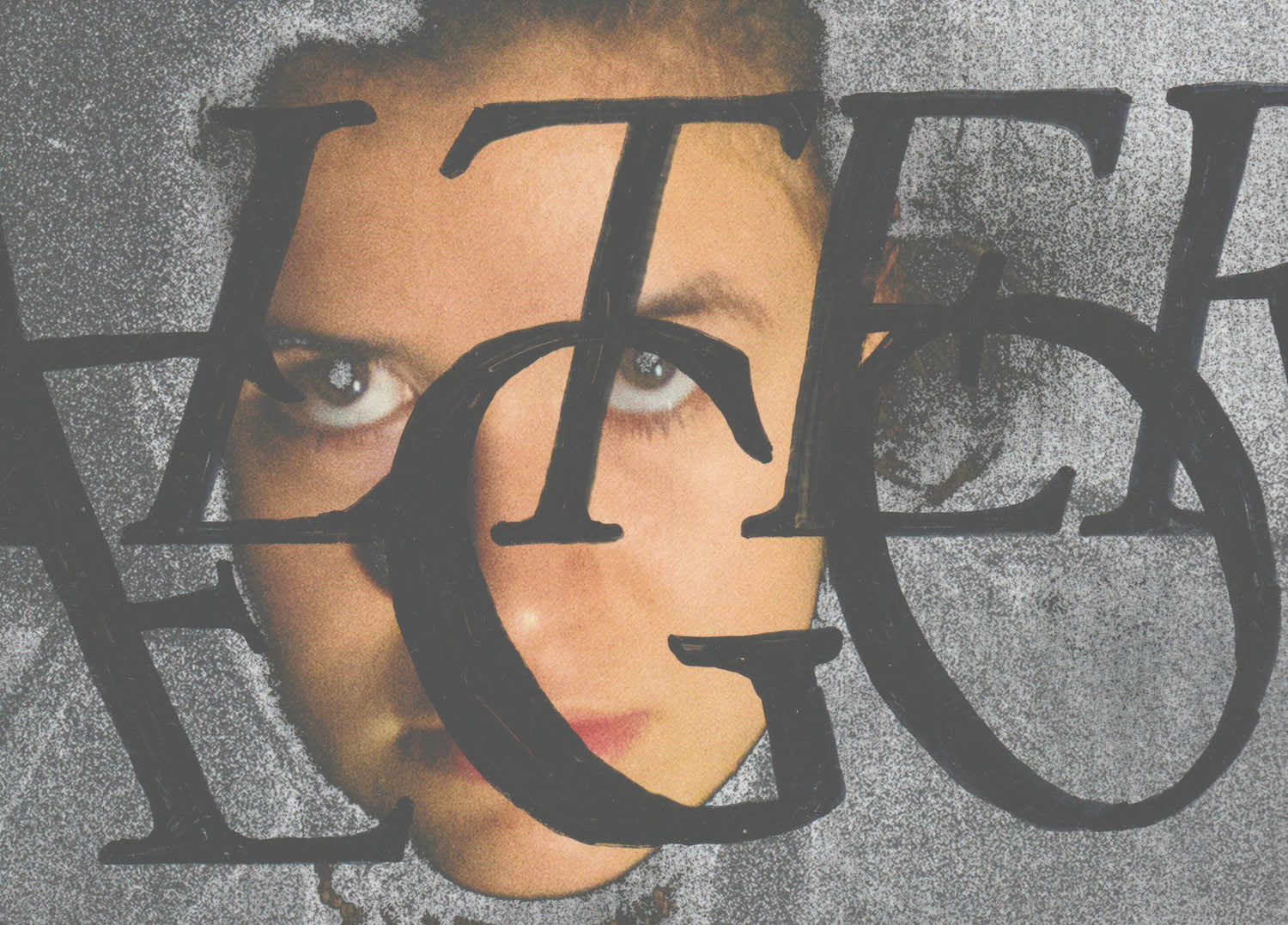

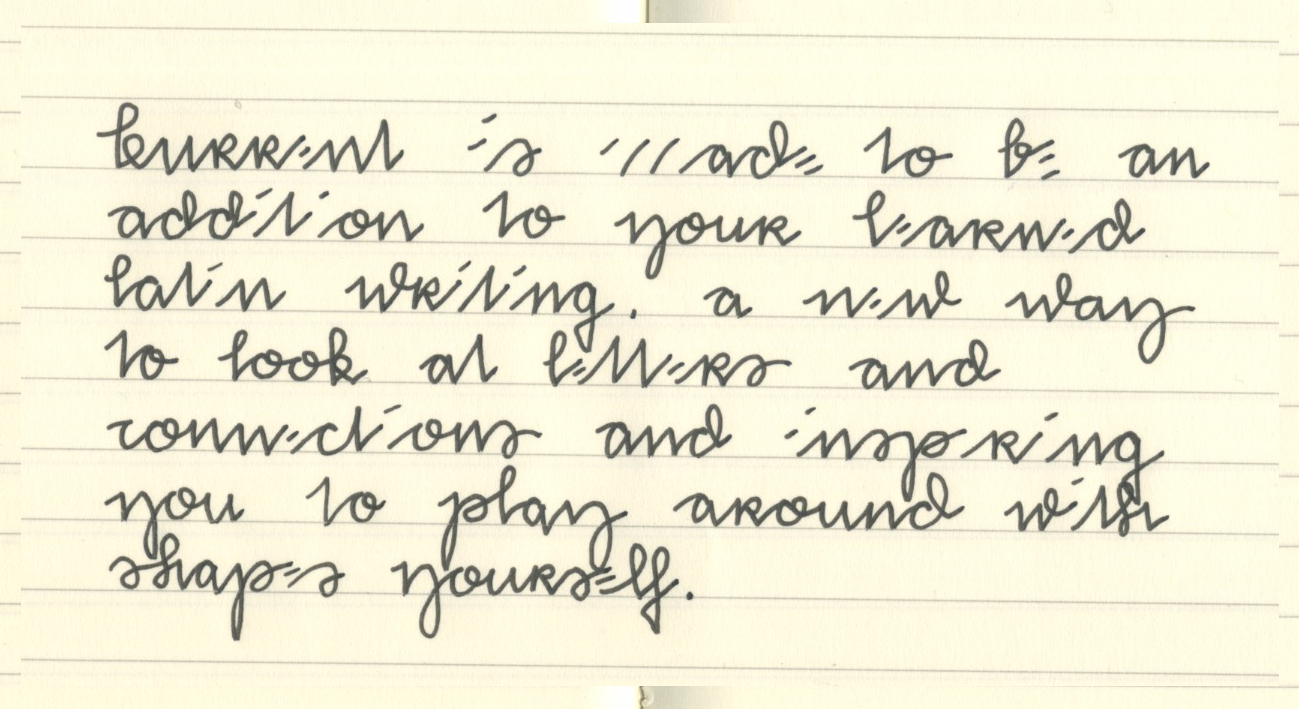

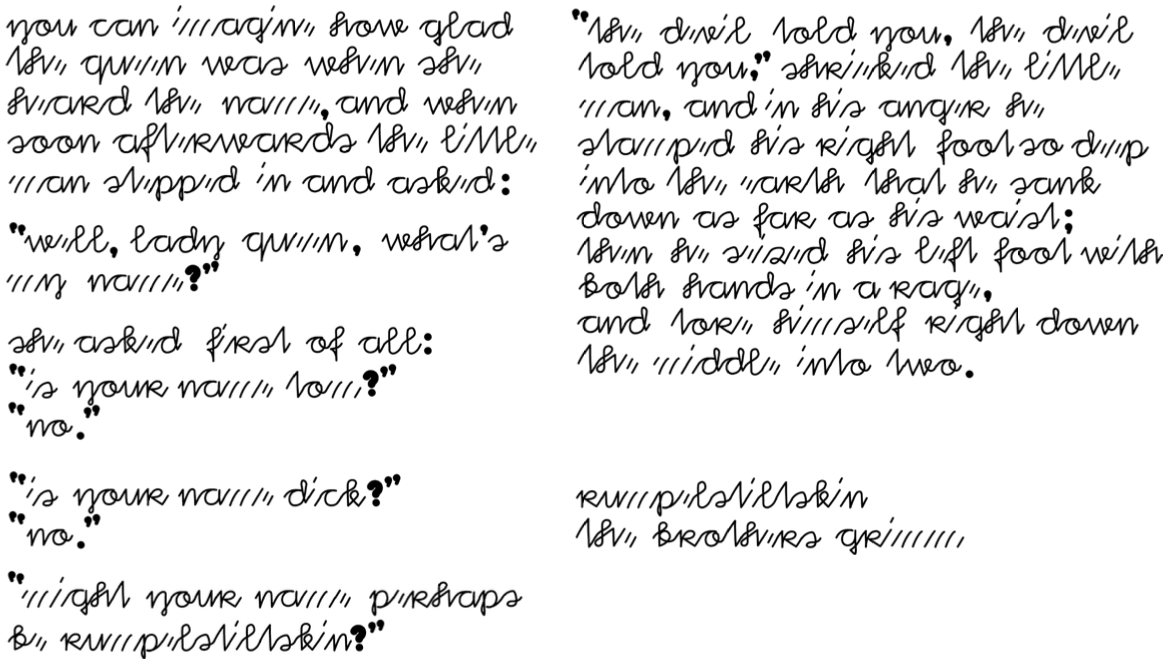

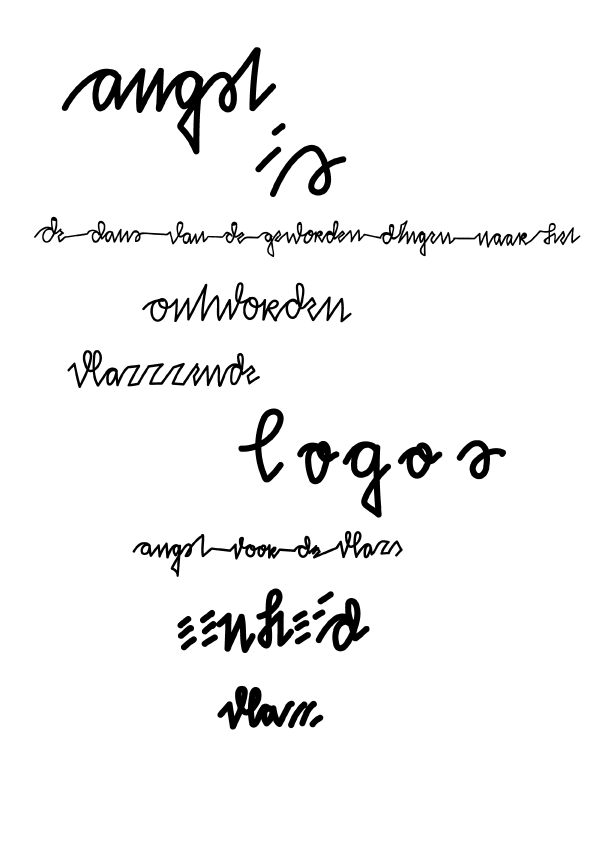

Kurrent applied to a typographic expressive poem by Paul van Ostaijen, a fragment of his book De Feesten van Angst en Pijn. It focuses on the expressive quality of the typeface, the details in the letters and the connections.

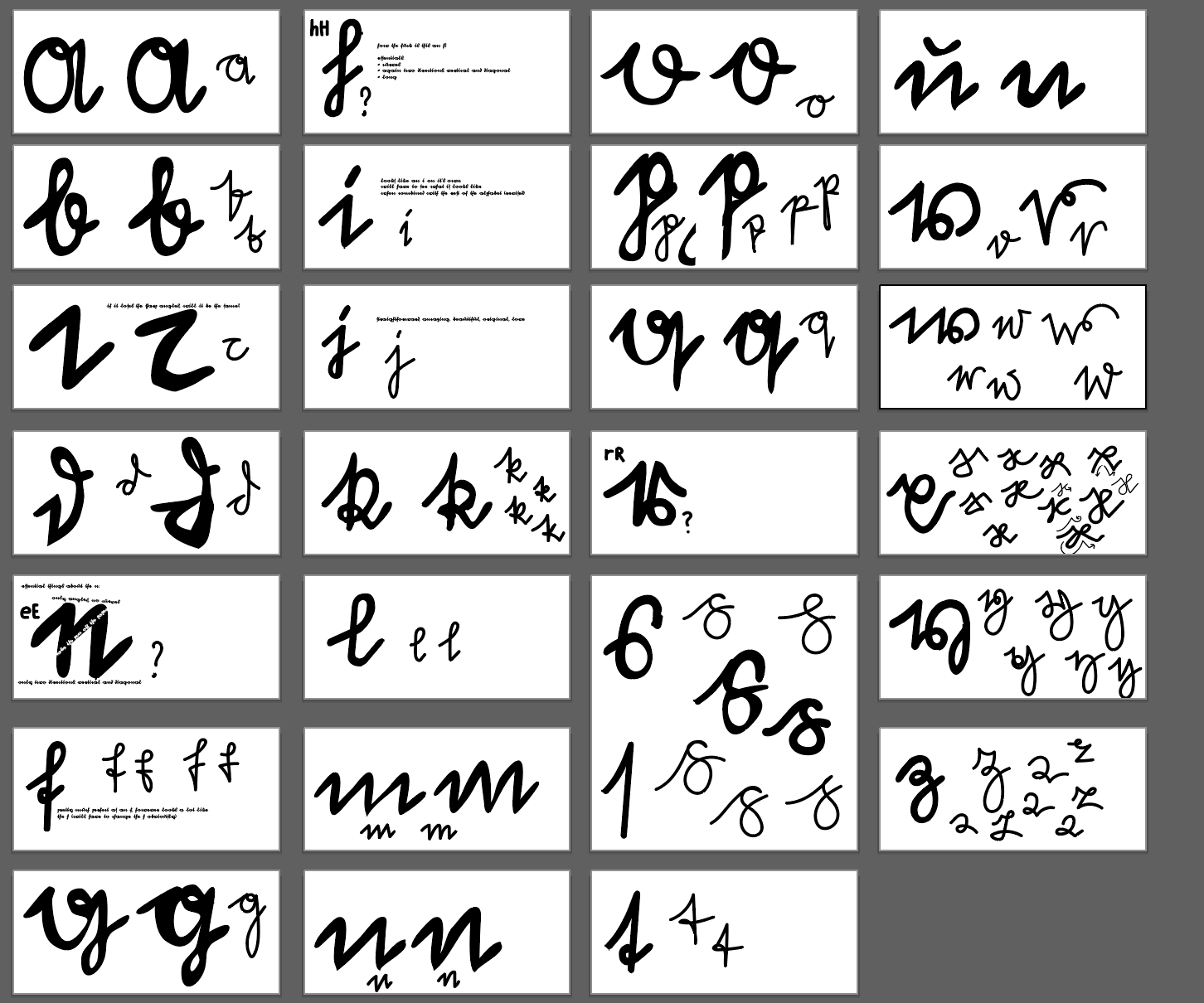

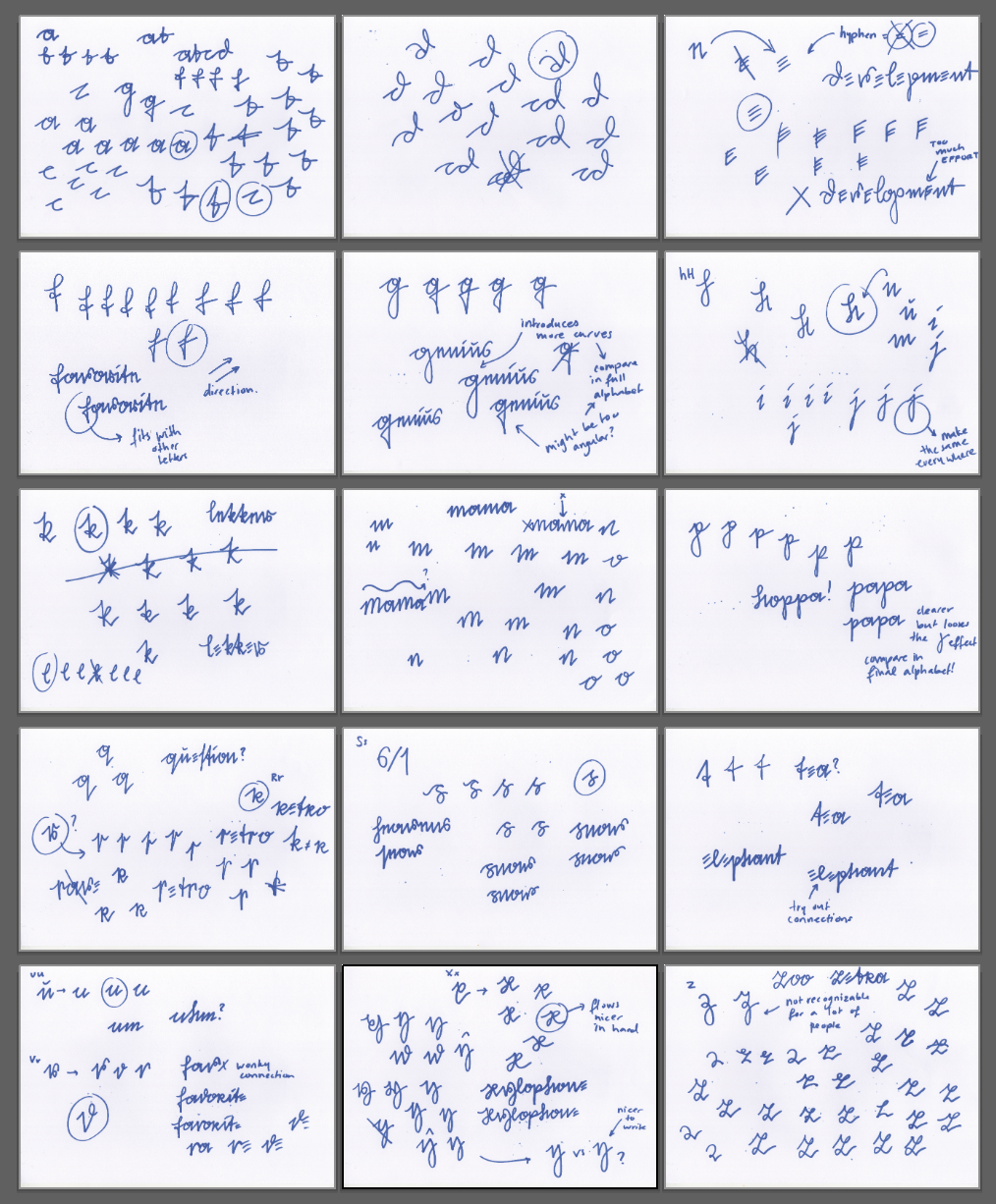

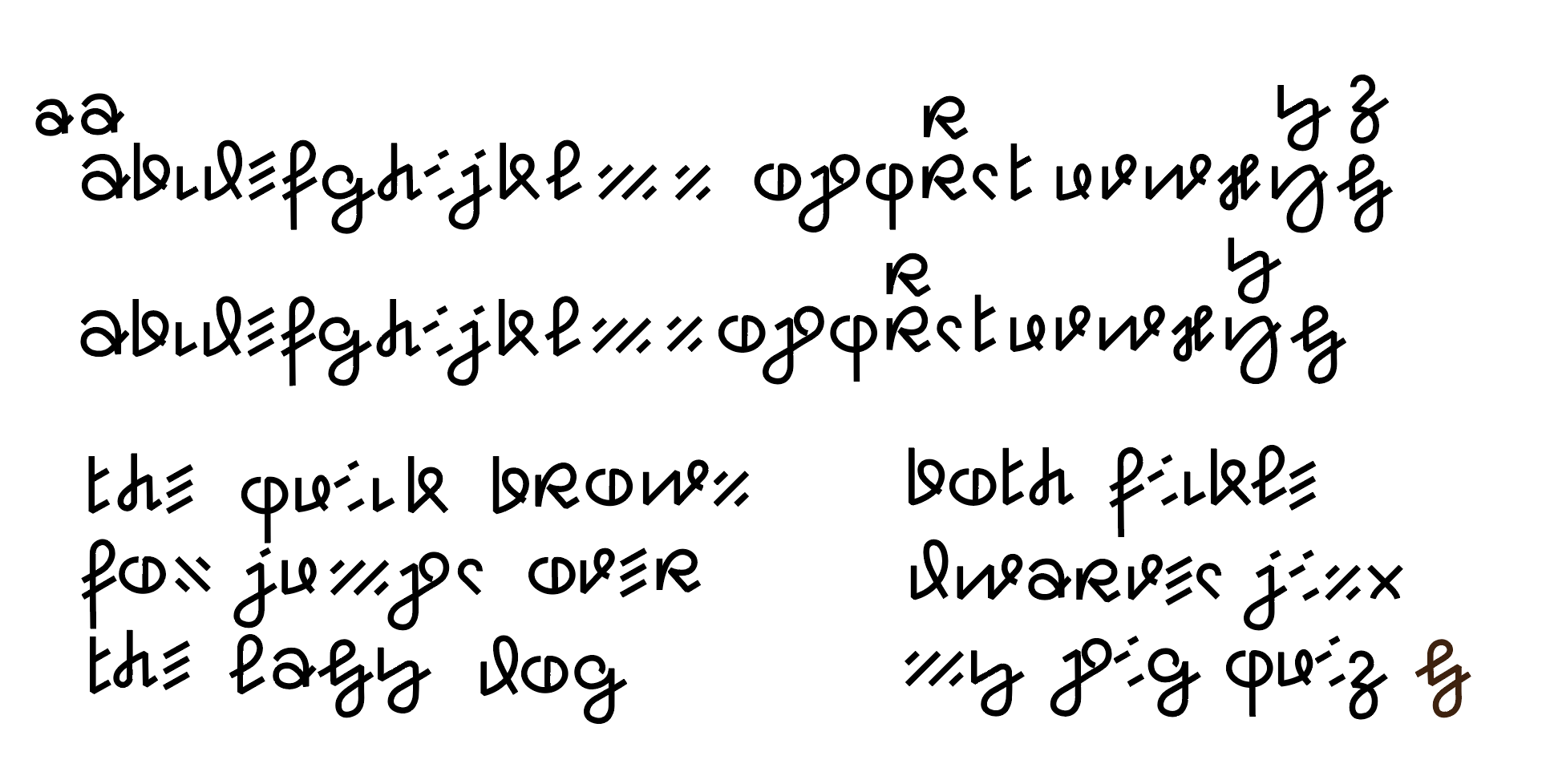

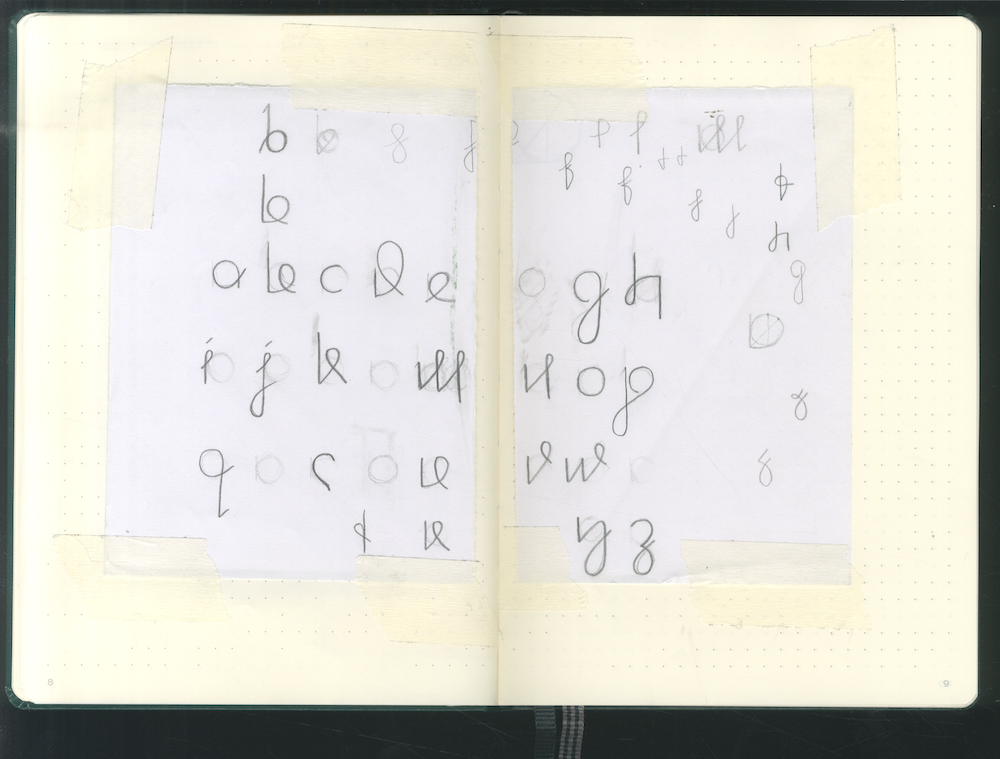

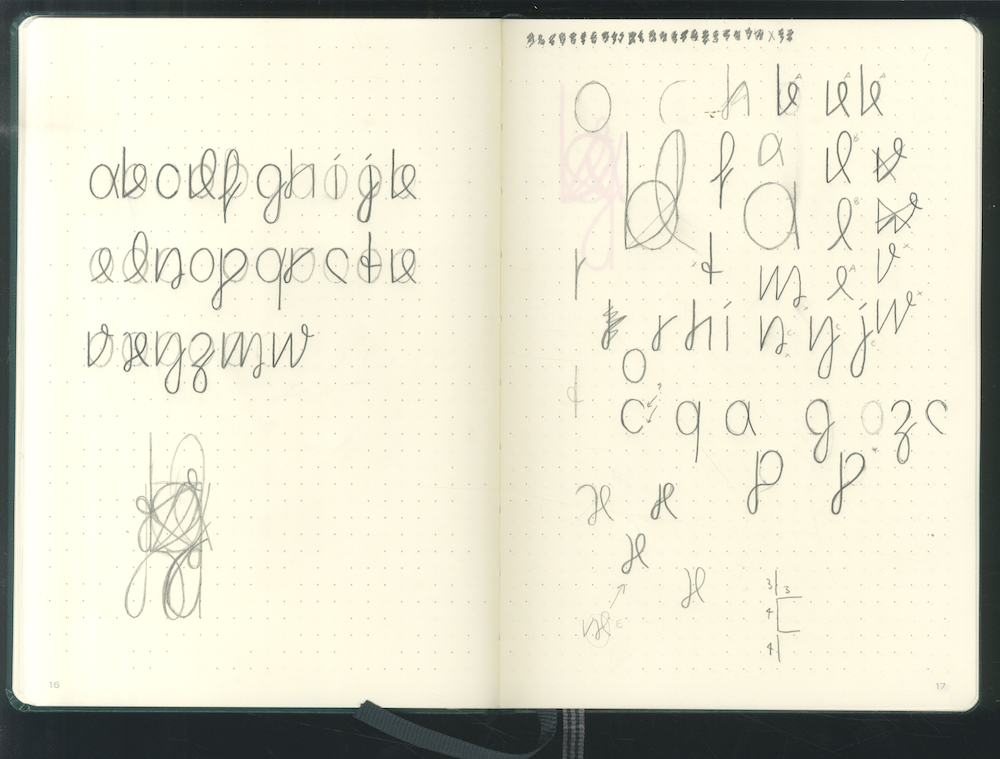

Kurrent is inspired by the old German Kurrentschrift, the handwriting version of Blackletter scripts. The shapes are based on the refined, more modernised version Sutterlin that was taught as the basic handwriting in German schools from 1915 to 1941.

In 1941, Sutterlin was removed from school curriculums by the Nazi regime and it never came back. Only the older generations still know how to write it. A strong type like this shouldn't be lost to the ages. It's graphic identity is unmatched across latin typefaces. Kurrent is a type developed as a new version of the old Sutterlin, to retain its sharp lines and delicate curves in modern times.

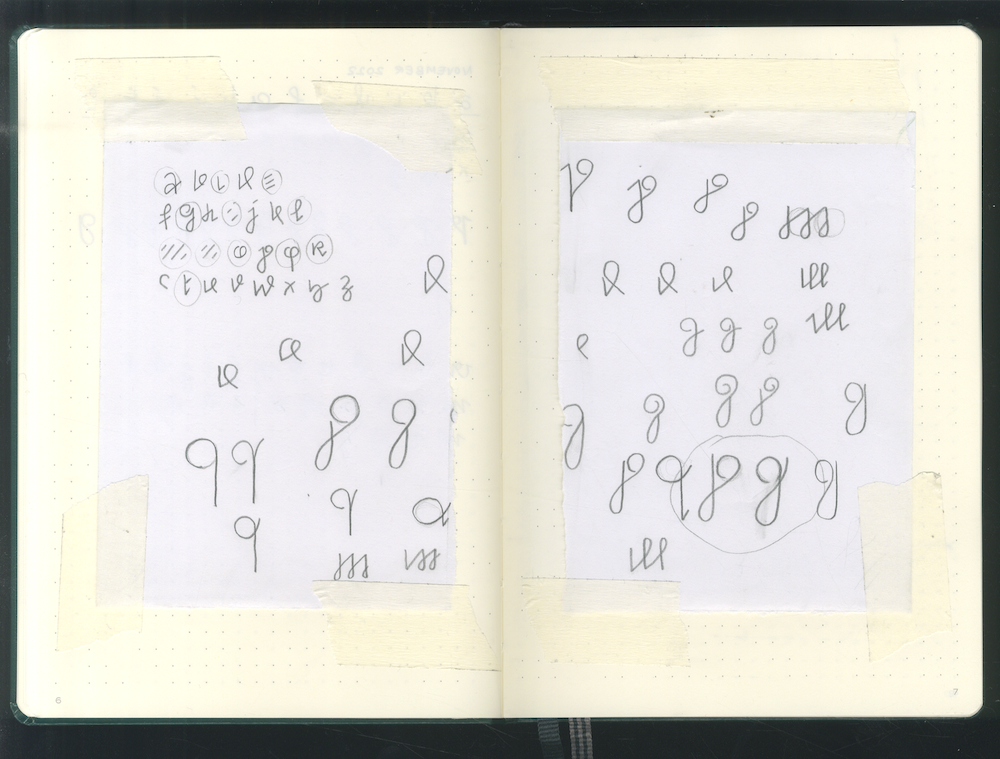

This project has turned into an ongoing typeface development. Who knows when I will finish. Below are the steps I slowly made in 2022/2023.

“You know that feeling when a guy sends you a text at two o’clock on a Tuesday night asking if he can come and find you and you’ve accidentally made it out like you’ve just got in yourself so you have to get out of bed, drink half a bottle of wine, get in the shower, shave everything, dig out some Agent Provocateur business, suspender belt the whole bit and wait by the door till the buzzer goes?” (1)

The 2016 show Fleabag begins in medias res with the above monologue, as the eponymous protagonist stares directly at you, breaking the fourth wall. It is a show where you are continuously engaged with the protagonist by the protagonist, as she turns to her audience to keep us up with the story, providing explanations or context for the current events. She uses us to briefly escape her life, simultaneously making us accomplices for her actions. While she tells us what she is thinking about or what she plans on doing next, there is no way for us to stop her.

The fourth wall traditionally guards the divide between spectator and participant. Now, fourth walls are manifested in our daily lives, and breaking the fourth wall is a normal occurrence. We, our mental and emotional beings, leave us, our physical bodies, behind, while we dive into entirely different worlds online.

Breaking the fourth wall has a long history in comedy, as the absurdity of the break can make it hard to incorporate it into serious fictional narratives. It is easier to use as a funny interlude, like Groucho Marx in Animal crackers (1930), or as sly commentary on occurring events, as Ferris does in Ferris Bueller’s day off (1986), but it can also establish a deep connection between actor and audience (when Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton shoot a helpless look at the audience and we instantly watch over them). Used like this, it will never allow us to actively take part in the story, as seen in Fleabag.

Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) is often accredited with making the technique of breaking the fourth wall into a critical and influential theatre convention. In his principle of Verfremdungseffekt (defamiliarisation effect), Brecht broke the fourth wall to distance the audience from the dramatic action going on in the play, to focus on the narration and connect it to the real world. He wanted the spectator to know they were in a theatre, creating a fiction in which the familiar was broken up, causing a sense of curiosity about the events. Watching his play, the audience would intellectually participate, contemplating along with the story.

Recently, the convention has become more popularised through mockumentaries like The Office (2005-2013), Parks and Recreation (2009-2015) and Modern Family (2009- 2020). Here, the characters speak their inner monologues directly into the camera as if in an interview for a documentary (while the interviewer is never shown or heard). We, as viewers, are not allowed into their actual private lives anymore as much as we have in shows or films before. Instead, we are shown a pumped-up version of the characters. They know they are being watched at all times, by the viewers but also amongst themselves, and thus change their behaviour accordingly. This changes the dynamic between spectator and participant, as the audience can never be sure what part of their fiction is supposedly real and what part is set up for the theatrics of the ‘documentary’.

This effect comes back in Fleabag, who is first and foremost a performer for the audience. She doesn’t change her behaviour as much as she tries to make excuses for it or comment on the fact that she should but won’t change her life. She uses us as a way to feel better about the things she does in her life, a way to conceal her wrongdoings f rom the other characters and herself, by talking her way out of them to the passive participants in her life.

Breaking the fourth wall in traditional performance media like theatre, films and shows always has the character stepping out into our world for a moment. With the rise of online media where everyone is free to participate as they please, a new way of breaking the fourth wall is occurring. The spectators enter the media and are able to adopt a new persona to their liking. The line between spectator and participant blurs and the intention behind the break now changes from person to person. We interact with other people in these media as different personalities, no longer tethered to our given body. We get the chance to completely reinvent ourselves, with little to no consequences and put up a show for the rest of the world to see and believe in.

A prime example of this is role-playing games, in which you select an avatar that will walk around in the computer world for you. These games increasingly have taken to the internet as well, for example as massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) like Runescape (2001), World of Warcraft (2004), and Fortnite (2017). This means you can now interact with people from all over the world with a persona of your choosing.

The increased blurring of the roles of spectator versus participant was showcased in April 2020. During the height of the lockdowns across the world, artists and people alike were figuring out a way to share their content with the world in these unfamiliar circumstances. Travis Scott created Astronomical, an online live concert, together with Fortnite. His audience could join the event as their Fortnite avatars and follow a digital Travis Scott taking over the gaming universe. It becomes visible now that there is a new kind of spectator/ participant divergence, in that there isn’t one. In media like games or social media, we are constantly actively participating in the show that we put on, while simultaneously watching other people put on that same show. We have broken the fourth wall in the opposite direction and have joined the fiction outside of our real world.

Games usually have an objective (find something, kill the bad guy, be the bad guy), like in war or fantasy games (Fortnite, Pokémon, etc.), which makes them at least slightly removed from real life. This makes it easier to separate reality from our on-screen fictions. However, there are also games without any clear objectives, like The Sims (2000) or Second Life (2003), ‘life-simulation games’ where the only objective is to just live life, and make life decisions for your avatar. Often, people like to make these decisions based on what they would do in real life since it is so alike. It could even be described as an interreality. Games like this have an increased risk of avatar identification, a temporary merging of the avatar and the sense of the self, as it becomes harder to tell apart your persona from your person.

“This is the whole game, and there is no way to win, except to keep yourself from becoming depressed. The Sims is an escapist vehicle for people who want to escape to where they already are [...]” (2)

Increasingly, we are losing touch with our bodies. We spend hours a day behind a screen, playing games, watching videos, scrolling through images. It’s almost easier to live a fulfilling life without a body than it is with one, as our online personas steadily grow stronger and more important, fed by the internet’s structure of avatars, usernames, asynchronous communication and anarchy. It is easy to get lost in a world where you are anonymous not only to other people but partly to yourself.

Fleabag talking to the camera has been described by experts as a way her mind escapes, perhaps involuntarily, from the situation her body is in, a phenomenon called dissociating. This is backed in the show’s second season, where we are introduced to the Hot Priest. He is the first side- character to notice Fleabag’s habit of shying away from life to talk — or just look — at us, as he interjects “Where’d you just go? You went somewhere.” He observes her drifting several times after this, so we can conclude that when Fleabag talks to us, she momentarily leaves her body to enter into our world to talk to her ‘friends’, the audience.

A person playing a game might feel similar, projecting themselves into the online world with their avatar as its own entity, rather than a shell directed by a real person behind a screen. This feeling is strengthened by the lack of use of their bodies. Our digital devices hold us in their grasp, we move through life independent from our passive body, and apart from occasional physical needs like hunger or an itch we can shrug off our sense of self and actively delve into our anonymous cyber-world. Because of this disengagement with the body, one might regard their internet actions as separate from who they are offline. These are things they didn’t really do, but someone that is not actually them, a different, detached and disembodied person, physically removed from oneself. This is described as the ‘online disinhibition effect’. (3)

The consequences that the physical world holds are not in effect in the digital world, and the participant can start acting completely different, knowing that they are safer to express themselves. The anonymity and invisibility for everyone, combined with no visual social clues from others, makes it easier to lose grips on what is perceived as ‘normal’ social behaviour and act in ways people would not do face-to-face. The intention behind stepping beyond the invisible wall changes with the medium and the person. It can be presented as sharing personal information with others quickly, trusting people in a way you can’t when they know your personal history within their context. It can also present oppositely, letting out anger and resentment, giving criticism, or even sending threats.

One phenomenon of the latter is dubbed the Internet Troll. A troll starts fights on social media or forums usually out of pure spite and for their own amusement. They might comment something unnecessarily rude on someone’s Instagram or Twitter post, usually someone famous with a lot of followers, often something that is hardly related or completely unrelated to the topic of the post. This leads to hundreds of replies by defensive people that will only entice the troll more, and they accomplish nothing but angry, frustrated internet users and their own fun. While this may come back in their day-to-day personality, Internet Trolls have an easier time expressing their malicious intent online because they find similar-minded people, anonymity and distance from themselves and their personal responsibility. Trolls’ intentions are different from those who use the internet to create their own narrative and act out their individual theatre piece. The troll tries to change the status quo of social media, they expose these fictions of others, they try to break them, hiding behind a force field of anonymity, materialised by their screen. It is as if someone would suddenly start to talk back to Fleabag when she is expecting no answer.

We can wonder now how this effect of being on the internet, dissociating from your body and entering a new world will affect the way we live in the future. Especially during the ongoing pandemic, it has become clear just how much of life we can experience from behind a computer. Many things that were previously analogue have seen the large scope of possibilities on the internet, from working-from-home to online events like Travis Scott’s concert. In the beginning, we were anxious to get back to the way things were and clumsy with our new routines, but many people have since accepted and even embraced the way the internet can work for us unlike anything before. With such a change in pace, and the many innovations creators and others alike have come up with to adapt to a new life online, it is hard to imagine we will ever fully go back to an absolute physical life.

This means that our presence on the internet will be greater than anything before. What will that mean for the way we behave and interact with others from now on? The escapism from real life we see on TV in shows like Fleabag is only magnified when we reverse the roles on ourselves, as we can change and excuse behaviour in any way we want. When most of life is online, and most of online can be modified and catered to every extent, how will we define something as real?

◆ 1 ◆ Fleabag, S1E1, BBC Three, 2016

◆ 2 ◆ Klosterman, Chuck. “Billy Sim” Sex, Drugs and Cocoa Puffs: A Low Culture Manifesto, 2003

◆ 3 ◆ Suler, John. “The Online Disinhibition Effect.” CyberPsychology & Behavior, vol. 7, no. 3, 2004, pp. 321-326

2021

Child.

My mother speaks in a patois of the southern part of the country, though she taught herself the ‘normal’ way of speaking long ago, when she moved to the big city in the north. Now, the southern patois only comes out on special occasions. Such as the birth of her first daughter, to be named child.

Child is a boy’s name. In her language anyway. This was difficult, as I am her daughter, and up in the north, in the 2000s, a boy’s name for a girl was very particular (the general north isn’t by far as cool and developed as they think). There is a feminine variety, a diminutive of the name. My mother didn’t believe I would be a diminutive person, thus I ended up with a boy’s name: child, for the non-diminutive person.

From my first year to my eleventh, almost all the people I would meet, would call me by the feminine variety of my name, not my name. When I entered high school, I finally started correcting them. I ended up a more diminutive person than my mother expected from me.

I started to understand that my name, while so ordinary to me, so gravely shifted the perspective of what was meant to be right and normal in other people that everyone I met did the same little theatre piece of pretending they don’t understand why I would have a boy’s name, to saying they thought it was ‘so fitting and beautiful’, to then never calling me by my actual name again.

The older I got, the more confidently I gave people my name. Now, the theatre piece has been reduced to exclaiming how great it is that I am breaking gender roles (as if it was my choice). I like to believe that it is because I like my name now, or at least I’ve grown into it, but I think it really is because people don’t take little girls with grown man names seriously. Only women with grown man names.

Prompt: What's your name?

2021

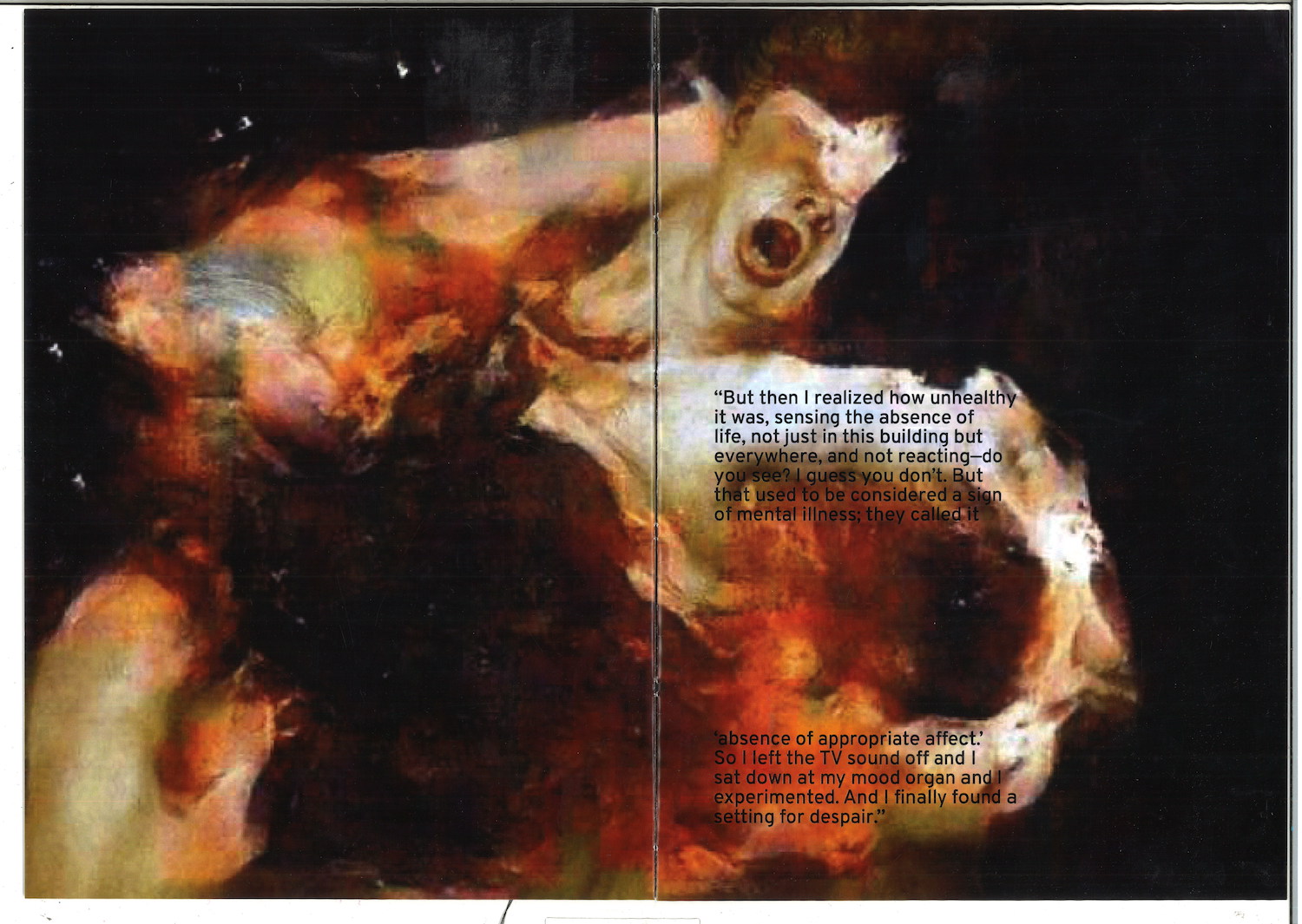

There’s a Noise, it’s insistent. I can hear muffled speaking and machinery, but the Noise is too loud to make out what it is. The machinery and voices stop. I can just hear the Noise now. I can’t even see. Such an insistent Noise.

I’m barely warned by the suction noise that means my house will be invaded, because the Noise overshadows it. Light and warmth flood my space. I squeeze my eyes closed and feel I’m being picked up. I zone out the actions. When I’m put back in my cold house I breathe again. The Noise is back.

2018

I am a killer.

A mass murderer.

I mutilate anyone I touch. And I touch everyone.

No one can escape the gentle caress of my fingers, the dancing embrace of my brilliance. And no one wants to. They like my warmth, my loving aura and my tender smile. They will lie with me, hold me close, whenever I am there. On the colder days, they are thrilled when I choose to wrap my arms around them and pull them in. But the warmer days are when they strip down for me and let me dive into their skin.

No one thinks about the effect I have on them, the way I inch them closer to their death with every touch I allow them to have. The way they hurt when they take too close a look, the way I burn when they enjoy my grasp too much, too long.

Some people try to resist me, my glow, my heat. They would to anything to protect themselves from my reach. But I am there, I will always be there. No one can escape my kiss.

In the end, everyone will regret the time they spent with me, some more so than others. And in the end, no one will be able to look at me again. They will replace me with artificial elements to try and imitate my body. But that’s okay, I have done my damage.

Sun

2018

A shoe is an item of footwear intended to protect and comfort the human foot while the wearer is doing various activities. Shoes are also used as an item of decoration and fashion. The design of shoes has varied enormously through time and from culture to culture, with appearance originally being tied to function. Additionally, fashion has often dictated many design elements, such as whether shoes have very high heels or flat ones. Contemporary footwear in the 2010s varies widely in style, complexity and cost. Basic sandals may consist of only a thin sole and simple strap and be sold for a low cost. High fashion shoes made by famous designers may be made of expensive materials, use complex construction and sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars a pair. Some shoes are designed for specific purposes, such as boots designed specifically for mountaineering or skiing. environmental hazards

Traditionally, shoes have been made from leather, wood or canvas, but in the 2010s, they are increasingly made from rubber, plastics, and other petrochemical-derived materials. Though the human foot is adapted to varied terrain and climate conditions, it is still vulnerable tosuch as sharp rocks and temperature extremes, which shoes protect against. Some shoes are worn as safety equipment, such as steel-soled boots which are required on construction sites.

Source: Wikipedia

2018

Christmas is coming, I think, as I stare down to the snow that fell this morning. It crunches under my feet when I walk. The night is cold now, not like it was during the summer, when I wanted the ice to cool me down. But during the summer we didn’t have any ice, not on the ground, not in the freezer, and we didn’t have the money to go to the store and get some. Now I don’t need the money, there is an abundance of ice on the streets. The flakes reflect the streetlights and the colours of the world. But those glittering gems are not enough anymore. I need something else. Now that my hands are tingling and my mouth can’t move, I need something else. I wish the sun was up in the sky, warming my face with her light. But it’s dark, the sky is clear and the stars are twinkling. There is a path shovelled through the snow. To walk. The pavement is wet and dark, like the atmosphere around me. The snow is white, shimmery, almost see through in its intensity. Don’t step on the broken glass. That’s what my mind tells me anyway. But I love the crunch. It calms me. There is an eerie ambience in the air tonight, the contrast between the dark sky, the dark road and the bright brilliance of the snow and the stars. Life isn’t meant to be black and white, yet abstraction is often only one floor above you. Black and white, like the way my mind jumps to conclusions and theories about situations I don’t remember. The memory we used to share is no longer coherent, but I still think about it. Mull it over in my head. Sometimes though, my head will not let me forget. When I was little, I had a car door slammed shut on my hand. I still remember it quite vividly. Maybe that’s where my problems lie. But I can’t ponder that too long, or I will fall down that spiral one too many times. A song can make or ruin a person’s day if they let it get to them. This is my song, and I will not sing. Where do random thoughts come from, and where do I go to get it shut off. My mother always told me to think happy thoughts. She was my rock, my center. But now it’s only my dad and me, and the old apple revels in his authority. I had to leave. And now the snow is crunching under my feet, and my hands are cold, and the sky is dark and I don’t know where to go. Think happy thoughts. Sometimes it’s better to just walk away from things and go back to them later. Random thoughts just come and go as they please, but they are always meaningful. Like: I often see the time 11:11 or 12:34 on clocks. I don’t know what it means, but I know it means something. They are extraordinary times on ordinary clocks. 11:11 is the time I was born. Years ago. Decennia. Where do these thoughts come from? Where do I come from? The snow crunches under my feet again, and my hands are still cold and my lips still won’t move, but my mind is going places. Now I need to too.

Prompt:

◆ I often see the time 11:11 or 12:34 on clocks.

◆ Christmas is coming.

◆ There was no ice cream in the freezer, nor did they have money to go to the store.

◆ Don't step on the broken glass.

◆ Sometimes it is better to just walk away from things and go back to them later.

◆ The memory we used to share is no longer coherent.

◆ The sky is clear; the stars are twinkling.

◆ Abstraction is often one floor above you.

◆ A song can make or ruin a person’s day if they let it get to them.

◆ A glittering gem is not enough.

◆ When I was little I had a car door slammed shut on my hand. I still remember it quite vividly.

◆ The old apple revels in its authority.

◆ Where do random thoughts come from?

Source: Random sentence generator

2018

I am a new media design student, based in Helsinki.

Interested in:

◆ Evolution of technology (and the forced rapid innovation and familiarisation in recent and coming years)

◆ Perpetual liminality of the modern world, the pausing and accelerating of time

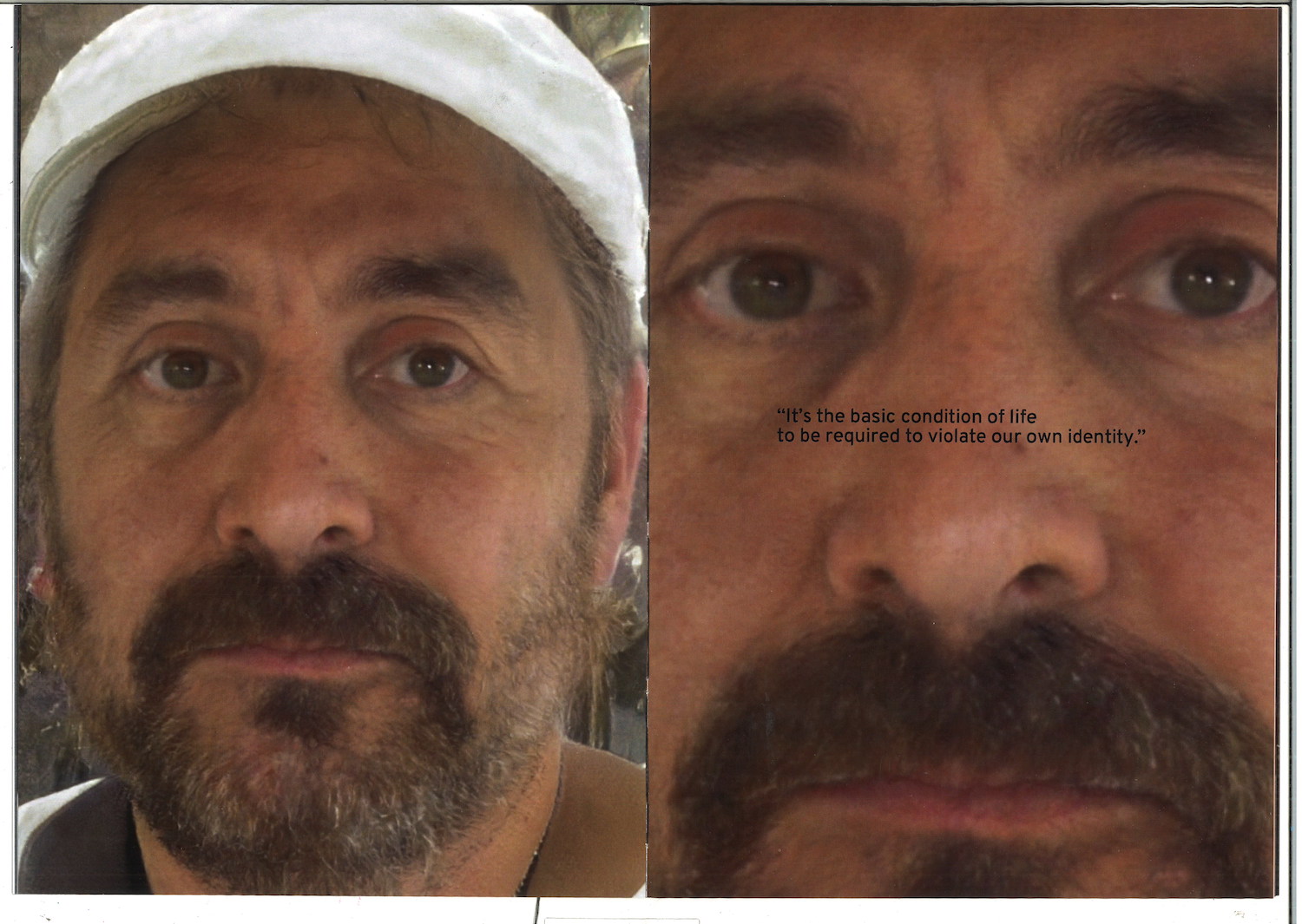

◆ Changing of identity within situations and times - alter egos and hidden egos

◆ Communication without a (human) body/identity, without a shared reality

◆ (Social) media culture and the effect on our sense of identitity

◆ How we live together with others and ourselves

◆ Research / Gamedesign / Webdesign / Editorial / Writing / Illustration

< cv >

Guus Hoeberechts

02-06-1999, Amsterdam (NL)

guus-99 [at] live [dot] nl

+358 40 144 52 54

Helsinki

<https://www.instagram.com/guus.eh/>

<https://vimeo.com/guuseh>

Education ☺︎

◆ 2017-2018 Royal Academy of Art The Hague (preparatory year)

◆ 2018-2022 Design Academy Eindhoven (communication BA)

◆ 2022-2024? Aalto University of Arts (new media MA)

Experiences ☺︎

◆ 2015 1-week internship Koeweiden Postma (Total Design) - graphic design

◆ 2016 2-day internship NERF Meubels op Maat - interior design

◆ 2019 exhibition Underexposed Underground, De Fabriek Eindhoven

◆ 2020 exhibition We never cycled to Dylan's, De Fabriek Eindhoven

◆ 2021 2-month internship <Outsiderland>/Outsiderwear Festival/Jan Hoek

◆ 2021-2022 5-month internship <The Hmm> - production and (graphic) design

◆ 2022-now production + programming <The Hmm>

Skills ☺︎

◆ Adobe Suite (photoshop, indesign, illustrator, premiere)

◆ HTML/CSS (intermediate)

◆ JavaScript (intermediate)

◆ Processing/Java (intermediate)

◆ ReactJS (beginner)

◆ Unity (beginner)

◆ Blender (beginner)

◆ Cinema4D (beginner)

◆ Dutch and English language (fluent)

guus-99 [at] live [dot] nl

+358 40 144 52 54

instagram @guus.eh